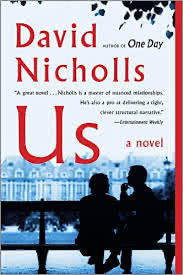

Us

Us

David Nicholls

396 pages, 2014

“It was dizzying, really, to be in love at last. Because this was the first time, I knew that now. Everything else had been a misdiagnosis – infatuation, obsession perhaps, but an entirely different condition to this. This was bliss; this was transformative.”

Despite pages of engaging writing about Douglas’ tireless love for Connie, David Nicholls’ novel, Us, functions more as a tale of unrequited love than of a mutual union. Douglas is the quintessential nerdy scientist whose unconventional sister, Karen, fixes him up with the whimsical free-spirit, Connie. Karen lures Douglas to her dinner party one evening, but Douglas hesitates since his sister’s orbit veers miles outside of Douglas’ laced up comfort zone: “Karen was promiscuous in her friendships and ran with what my parents referred to as ‘an arty crowd’: would-be actors, playwrights and poets, musicians, dancers, glamorous young people pursuing impractical careers, staying up late then meeting for long and emotional cups of tea during all hours of the working day. For my sister, life was one long group hug and it seemed to amuse her in some obscure way to parade me in front of her younger friends. She liked to say I skipped youth and leapt straight into middle age…” And so begins a series of endless contrasts between Douglas’ unshakable stiffness and Connie’s passion for drawing outside of the lines. Douglas is instantly smitten, Connie is rebounding, they date, marry and move to the country.

The plot opens with Connie informing Douglas that, now that their teenage son, Albie, is finished with school and preparing to launch their English countryside nest, she feels their marriage has run its course. Connie prepares to separate, but agrees to make good on a long planned family trip through Europe with Douglas and Albie to celebrate his graduation. Connie views the voyage as a last hurrah. Douglas views the trip as a last ditch effort to re-spark the flame. The novel follows this volatile family through Europe, telling the tale through Douglas’ desperate perspective. Efforts to loosen his fundamentally uptight personality in hopes that he will win Connie’s heart are interspersed with flashbacks to their meeting, early courtship, and the arc of their unlikely marriage.

From a psychological perspective, Us makes some noteworthy observations about marriage, relationships, and the challenge of balancing separateness and togetherness. Douglas is so infatuated with Connie that he loses himself and any redeeming qualities he once possessed through his over-emphasis on his unending devotion. “For the most part I did agree with Connie. But if Connie had been arguing for a moon made entirely of cheese, I would have agreed with her too.” If only Douglas could rein in his infatuation long enough to exist as a separate self, maybe Connie could finally breathe deeply enough to appreciate his intelligence, self-deprecating humor and honorable devotion. Connie’s rejection of poor, pathetic Douglas has such consistency that she, too, loses herself in a consistent urge to push him away. For example, Connie becomes so disenchanted by Douglas’ decision to take a higher paying, less exotic job that she fails to reflect on her own failure to pick up a paint brush and pursue meaningful work of her own. Readers may sense they have entered a modern day Of Human Bondage. Connie and Douglas represent an extreme template for how fear of abandonment and fear of engulfment can play out in relationships. If only Douglas could take Connie’s advice: “Connie always said I was at my most attractive when I talked about my work, and she’d encourage me to describe it long after she’d ceased to comprehend the subject matter. ‘The lights come on,’ she said. As the nature of my employment changed those lights flickered somewhat, but initially she valued the many differences between us – art and science, sensibility and sense – because after all, who wants to fall in love with their own reflection?”

What this novel does best is use extremes to illuminate a psychological challenge faced by so many couples — the blurring of separateness and togetherness and the importance of remaining independent enough to be truly intimate. True, most couples face this challenge in more subtle incarnations, but through the extremes of this unfulfilling marriage, the importance of developing an independent sense of self is emphasized and eventually celebrated. Readers who enjoyed Nicholls’ One Day which became the film of the same title starring Anne Hathaway and Hugh Grant will notice similar relational dynamics, only with genders reversed. The novel’s conclusion beckons a sequel in which Douglas might just get his groove back.