Lost in Translation

“Emotional affairs” are complicated, controversial and difficult to define. When a married person begins developing strong feelings for a possible romantic partner who is not their spouse, the emotional pull may be subtle at first and often accompanied by feelings of growth and vitality. Interestingly, sometimes the spouse may notice a romantic dimension of the budding relationship before the partner who is engaging in the emotional affair realizes the attraction.

Emotional affairs are a common discussion point in individual and couples therapy. The late and respected researcher, Dr. Shirley Glass wrote a groundbreaking book, Not Just Friends, which offers excellent advice and parameters about emotional infidelity. People locked in an emotional affair will often exclaim that they are “just friends” and want the constructs of their marriage to allow for friendship. Through studying Dr. Glass’ work, I notice it is helpful to ask people deadlocked on this topic if the person they are fighting about is a “friend of the marriage”. Most of the time, if someone is having an emotional affair and in denial about the impact of the relationship, this question penetrates the conflict. Despite defending the friend and the friendship, there is often a sudden willingness to acknowledge that the “friend” is not a “friend of the marriage”. This acknowledgement often helps a couple re-direct and repair.

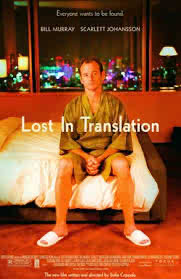

Sophia Coppola’s critically acclaimed 2003 film, Lost in Translation, tells a funny, visually seductive and compelling tale of an emotional affair to remember. The film won the 2004 Academy Award for best screenplay, and the believable dialogue animates and enlivens the characters. Bill Murray is perfect as Bob, a past-his-prime American celebrity who travels to Tokyo to cash in on a mildly humiliating assignment to sell Japanese Suntory whisky. Scarlett Johansson, although only 18 at the time of filming, is convincing as 25 year old Charlotte, who is killing time in the glitzy Japanese hotel while her husband works on assignment as a photographer. Charlotte’s husband is pre-occupied with his work, barely looks Charlotte in the eye, and has not noticed how lost and displaced she has become, trailing along in his shadow.

Between Bob and his wife’s empty telephone discussions and faxes (it was 2003 so no smart phones!) about color swatches and trivial home decorating decisions, and Charlotte’s husband’s star-struck behavior around a starlet he photographs, viewers understand Bob and Charlotte’s unexpected, blossoming bond.

Their chemistry begins with stolen glances in the hotel bar. Their banter is friendly but flirty, and their body language communicates an attraction. An unspoken boundary remains in place that prevents the relationship from becoming sexual. Bob and Charlotte are sexy and sensual with one another, but an invisible line exists between them, and is never crossed. Interestingly, when they say goodbye, both characters seem energized, revitalized, and ready to resume their married lives.

If an emotional affair unfolds, but the desire to salvage the marriage is solid, it is possible to incorporate the strengths and vitality of the affair back into one’s self and one’s marriage. For this strategy to work, the affair must end. Lost In Translation’s plot illuminates the complex and unexpected dynamics of emotional infidelity. I would never encourage someone to have an emotional affair. But Copploa’s film convincingly explores the possibility that there are ways to learn and grow from the experience and move forward with strength and marital commitm