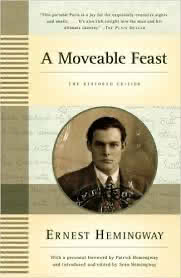

A Moveable Feast

The therapeutic benefits of writing have been touted and encouraged by clinicians for decades. Research continues to demonstrate that writing can improve mood and help alleviate depression. Newer research proposes that writing and then editing and revising a personal narrative can become a catalyst for individual change and increased levels of happiness.

Reading Earnest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, I found myself focused on the relationship between the writer and his mood. The book is praised and beloved as a magical celebration of Paris in in the 1920s at its peak of creative and artistic genius, but it is also a book about writing and the internal psychological experience. Readers are invited to descend the tunnels of angst Hemingway experiences when he feels creatively blocked and questions his abilities. Equally moving are the introspective and reflective passages that make Paris come alive:

…You could always go into the Luxembourg museum and all the paintings were heightened and clearer and more beautiful if you were belly-empty, hallow-hungry. I learned to understand Cezanne much better and to see truly how he made landscapes when I was hungry. I used to wonder if he were hungry too when he painted; but I thought it was possibly only that he had forgotten to eat. It was one of those unsound but illuminating thoughts you have when you have been sleepless or hungry. Later I thought Cezanne was probably hungry in a different way.

The book reflects on the early years of Hemingway’s first marriage, and reads at times as if he is attempting to write and re-write his personal narrative in order to make sense out of his past and the pain he may have inflicted upon others:

The last year in the mountains new people came deep into our lives and nothing was ever the same again. The winter of the avalanches was like a happy and innocent winter in childhood compared to that winter and the murderous summer that was to follow. Hadley and I had become too confident in each other and careless in our confidence and pride. In the mechanics of how this was penetrated I have never tried to apportion the blame, except my own part, and that was clearer all my life. The bulldozing of three people’s hearts to destroy one happiness and build another and the love and the good work and all that came out of it is not part of this book. I wrote it and left it out. It is a complicated, valuable and instructive story. How it all ended, finally, has nothing to do with this either. Any blame in that was mine to take and possess and understand. The only one, Hadley, who had no possible blame, ever, came well out of it finally and married a much finer man than I ever was or could hope to be and is happy and deserves it and that was one good and lasting thing that came of that year.

I wonder about the sincerity of these words and how they might be therapeutic or meaningful to others who find themselves in the peak of struggles with infidelity or marital distress. Many divorces are necessary, other marriages can be saved. The decision is never up to the therapist or the family or the friends. But journaling can be a meaningful way to attempt to sort out an experience while it is happening, not just in retrospect. Hopefully, Hemingway’s words and reflections were a comfort to him but might also be a meaningful catalyst for others.