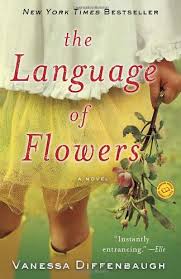

The Language of Flowers

THE LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS

2011, 338 pages, Random House, Vanessa Diffenbaugh

It is a basic principle of most forms of psychotherapy that it is often essential to examine how formative childhood events and primary family relationships relate to current life experiences. If you are curious about or currently examining how your own past informs your present, Vanessa Diffenbaugh’s novel, The Language of Flowers, is worthwhile reading.

This intense and emotionally raw story begins with its heroine Victoria’s eighteenth birthday. She has aged out of the foster care system and has nowhere to go. Having failed multiple attempts to become adopted, Victoria has no true connections and no resources other than her consuming passion for flowers. She begins to grow a small hidden garden in the San Francisco park where she sleeps, and when what little money she has is gone, she puts her floral intuition to work and secures a job with a local florist. The tale that unfolds alternates between Victoria’s heartbreaking past and her severely isolated present.

Victoria’s sentiments about the dysfunctional but well-intended system that raised her capture the lasting impact of a childhood without a consistent parent-child bond:

“I was filled with nervous anticipation, the feeling similar to what I’d experienced as a young girl on the eve of each new adoptive placement. Now, as an adult, my hopes for the future were simple: I wanted to be alone, and to be surrounded by flowers.”

Victoria’s name references the Victorian era’s use of flowers to communicate meaning, and the novel includes a comprehensive dictionary decoding the engaging language that flowers can speak. Victoria methodically compiles and references this dictionary throughout the story:

“I’d discovered the Romantic poets often referenced the language of flowers, and read everything I could get my hands on. The pages of the book were earmarked with notes scribbled in the margins. The poem I opened was eleven verses, all beginning with the words Love me. I was surprised. I had read the poem, I was sure, but I didn’t remember the dozens of references to love, only the flowers.”

The actual dictionary was compiled, in part, by Diffenbaugh who not only shares her heroine’s passion for flowers, but who is a foster mother herself and used the advance proceeds of this book to help create the Camellia Network, an advocacy group for girls aging out of foster care.

Victoria’s ability to communicate through flowers — a gift she learned from the foster parent with whom she came closest to adoption — leads to a series of heartwarming and whimsical interactions and sub-plots. These amusing and engaging tertiary characters, combined with the novel’s back-story, may give readers the impression that this book was written to become a film. But what Diffenbaugh does best is explore how the most painful and beautiful aspects of one’s past can resurface in unpredictable but meaningful forms. Without a childhood experience of unconditional love, intimacy is fraught with conflicting emotions. A secure attachment is still possible, but healthy emotions are much harder to recognize and sustain:

“I wanted to tell her that I had never loved anyone…But even as I thought the words, I knew they were not the truth. I had loved, more than once. I just hadn’t recognized the emotion for what it was until I had done everything within my power to destroy it.”

Diffenbaugh also comprehends that when two people genuinely understand each other’s past and share similar stories, their bond can be filled with obstacles but has the potential to become transformative. While Victoria’s history and its impact are extreme, Diffenbaugh’s sense of how the past informs the present is both psychologically compelling and memorable.