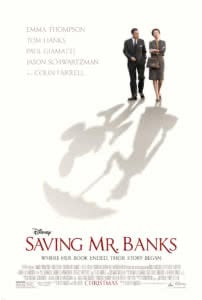

Saving Mr. Banks

125 minutes, Directed by John Lee Hancock, 2013

When I sat down last night to watch Saving Mr. Banks with my family, my expectations were modest at best. I felt pleased to find a rare PG rating without the 13 attached, and viewed our selection as an appropriate, child-oriented, family compromise. We have always appreciated the story of Mary Poppins, so learning the back-story of the adaptation of the book into a film intrigued us all.

I was completely unprepared for the power and psychological depth of this film.

Based on the tale of Walt Disney’s (Tom Hanks) 20 year effort to convince author P.L. Travers (Emma Thompson) to sign over the rights over her beloved book, the film is a dual track tale about fathers and daughters. On the surface, it is about Walt Disney’s desire to fulfill his daughters’ wish to make a film about a book they loved. His determination to make this story fly off of the pages and into a film despite tremendous resistance from Travers is an obvious and even gratuitous testament to boundless fatherly love. The tense but animated (pun intended) creative process of the film’s creation is pure family entertainment. On a deeper level, Saving Mr. Banks is about the lasting influence that fathers have on their daughters as told through the flashbacks to P.L. Travers’ childhood and her intense and at times troubled bond with her alcoholic father.

While working in Disney’s office in Los Angeles in 1961 to collaborate on the adaptation of the film, Travers continues to flash back to her traumatic childhood. Her memories crystalize the viewer’s understanding of the inspiration for her classic tale. Travers’ childhood experience tells a psychologically compelling story about how growing up in an alcoholic family produces scars that may never fully heal. Her past lingers in her present and influences her conscious and unconscious experiences in her approach to the world.

Saving Mr. Banks alludes to and explores an interesting psychological concept called sublimation. Sublimation is a mature and resilient coping mechanism in which pathological impulses or traumatic experiences are transformed into socially acceptable actions or creations. Such actions or creations have the healing potential to convert impulses and mend old wounds. It becomes obvious that Travers wrote Mary Poppins in order to work through her past and celebrate her father’s creative energy and unmet potential. According to the tale in this film, P.L. Travers’ father was a raging alcoholic who worked at a local bank, hence the symbolism in the choice for the Banks family name. The film implies that Travers’ writing Mary Poppins was sublimation at is best. As Tavers clashes with Disney’s script writers and song writers in the adaptation process, the author’s determination to redeem her father through preserving Mr. Banks’ character in the film becomes a crucial culmination of her healing process. Travers’ love for her father and desire to heal old wounds is a bittersweet story that will stay with viewers. If you are struggling with the legacy of a parent’s alcohol addiction, this film may evoke a range of emotions, but may ultimately be exceptionally therapeutic.