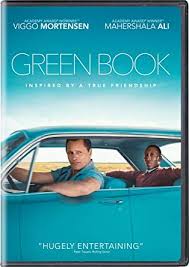

Green Book

The general commentary surrounding the Academy Award winning film Green Book zooms in on Hollywood, race relations and the historical details related to legendary musician Dr. Don Shirley, his driver, Tony Vallelonga, and their travels on a concert tour through the deep south in 1962. From a psychological perspective, a compelling and less discussed dimension of the film is its exploration of a quintessentially 1960s marriage as described from a son’s perspective. Green Book’s screenplay is written by Nick Vallelonga, the protagonist’s son; Tony and Delores’ marriage functions as a tertiary but meaningful anchor to the story.

The film opens as Tony Vallelonga (a convincing Viggo Mortensen) gets into an impulsive brawl and loses his job as a bouncer in a local club. When Don (played meticulously by Mahershala Ali), an eccentric musical prodigy, offers Tony a job as his driver, he communicates a list of conditions about the possible job. It initially must include laundering and ironing Don’s scrupulous wardrobe, but Tony sets a quick boundary explaining that such typical woman’s work will not be an option. He demands more money, turns down the job, and marches out of Don’s extravagantly appointed home. Undeterred, Don telephones the Vallelonga household and Tony answers the phone. Don asks to speak with Delores, and a brief exchange unfolds. Don respectfully thanks Delores for allowing her husband to spend eight weeks on the road with him, and meets all of Tony’s conditions. Don and Delores don’t bother consult with Tony; they agree in solidarity that Tony will take this job.

The couple exchange goodbye kisses and hugs, and Delores makes it clear that she expects Tony to write to her at each local tour stop. Tony resists, explaining that he won’t know what to say. Delores insists and points out that mail is less expensive than a long distance phone call. As Tony departs, Delores tells Tony that if he is not home for Christmas Eve dinner, he should not bother coming home at all. The two lovingly embrace, and Tony hits the road.

Predictable racial tensions are explored at each gig on the tour. But the quiet moments during which Tony attempts to write to Delores frame the narrative. He knows he wants to sign each letter “ps. Kiss the kids”. But Tony is otherwise at a loss for words. In classic Cyrano de Bergerac style, Don synthesizes Tony’s quirky personality into exquisite, poetic prose. He fills in Tony’s awkward blanks with heartfelt, magical descriptions of the trip. He channels Tony, but finesses the language just enough to remain remotely plausible, professing his love and longing to reunite with his beloved.

Regardless of whether this particular dimension of the story is true to history, it demonstrates the drawbacks and potential of long distance relationships that have grown more common in today’s modern era. More and more mothers work outside of the home and a growing number of families include two members must who prioritize their career. Long distance marriages and marriages that involve frequent travel have become commonplace. Especially in Washington, DC where I practice as a couples therapist.

The two months that Tony is away from his wife and children strain the marriage. But Tony’s letters shift the dynamic and elevate the dialogue. It matters less that Don is the one writing the letters and more that Tony is carving out the time to do something that makes him uncomfortable. His willingness to try something new allows the couple to connect on a deeper level. Don’s genius flows through Tony with a layer of sentiment that is true to both men and to Tony’s marital love. When the couple reunites, they seem to have grown closer through this new compartment of their union. They have improved their ability to balance separateness and togetherness and matured emotionally along this journey.