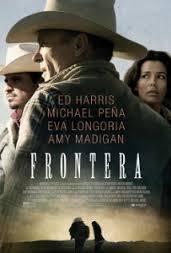

Frontera

Michael Berry’s timely new film, Frontera, is sure to stir controversy and conversation. The film’s backdrop is the border between Mexico and Arizona where Ed Harris plays a retired Sheriff living on an expansive ranch with his wife (Amy Madigan). The couple have a deliberately independent and horse-centered life and one of their ongoing conversations centers on when Harris will fix the fence on their property which is constantly compromised by illegal border crossings. In one of the film’s opening scenes, Madigan is killed in a scuttle near the boarder, and all circumstantial evidence points toward Michael Pena. Pena plays a hard working Mexican family man crossing into Arizona with hopes of finding gainful employment and ideally helping his wife (Eva Longoria) join him in the US in time for their unborn child to be born as a US citizen.

As the investigation unfolds, this film dares to ask unsettling questions and portray graphic dimensions of the tremendous risks people are willing to take, and the horrifying suffering many undergo, just to take a chance on gaining US citizenship. Frontera’s primary plot is the controversy surrounding Mexican border crossings and the many layers and angles of this issue. Its parallel sub-plot is the grieving process and Harris’ riveting performance as an anti-immigration grieving husband illuminates some interesting truths about grief and loss:

The Face of Grief is Not Predictable and Denial is Common

Harris’ immediate response to his wife’s untimely death is total silence and shock. Friends rush to his side to offer comfort. But stone-faced Harris seems almost indifferent to his loss. While presenting as grossly removed from his wife’s tragic accident, his failure to emote rings true. As a therapist, many of my clients have recalled a similar response to the loss of a loved one. A therapy client in his twenties who recently lost a parent explained:

“In my family, I’m the doer. I planned Dad’s funeral, gave his eulogy, and was the only one who could hold a coherent conversation with our extended family and circle of friends. I kept the house stocked with food and made sure mom was eating and sleeping. I was back in the office two weeks later and honestly thought I was okay. Almost a year later, on Father’s Day, it hit me. I actually forgot he was gone and I started searching online for an ecard. When I realized what I was doing I completely lost it. I could barely get out of bed for a week.”

Finding a Place to Direct One’s Energy Can Prove Healing

Harris immerses himself into the investigation of his wife’s accident. Despite the xenophobia and resistance of others, Harris persists. While many around him wish he would face his loss and leave the investigation to his former colleagues at the Sheriff’s Department, Harris’ efforts prove to be healing and restorative. In my therapy practice, many grieving clients report that were it not for careers that they love or other key projects they undertake, they could not move through the grieving process and come out the other side.

When Grieving, Help Can Surface in the Most Surprising Places

Grieving a loss does not come with a guidebook. Some find Elisabeth Kubler Ross’ books on grieving or Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking to be essential resources. John Irving’s A Widow for One Year and Isabel Allende’s Paula have also helped many of my clients during the early stages of grief. Harris delves more deeply into the circumstances and evidence of the incident in question, and his views about immigration evolve (somewhat). In this mode he finds comfort and camaraderie where he would least expect it.

The film’s final solution to the immigration controversy is at best trite and over-simplified and worst offensive. However, Frontera asks difficult questions and engages in a meaningful exploration of one of this countries’ most complex issues. Along the way, a moving essay on grief and loss unfolds.

If you are struggling with the death of a loved one, don’t miss this memorable film.